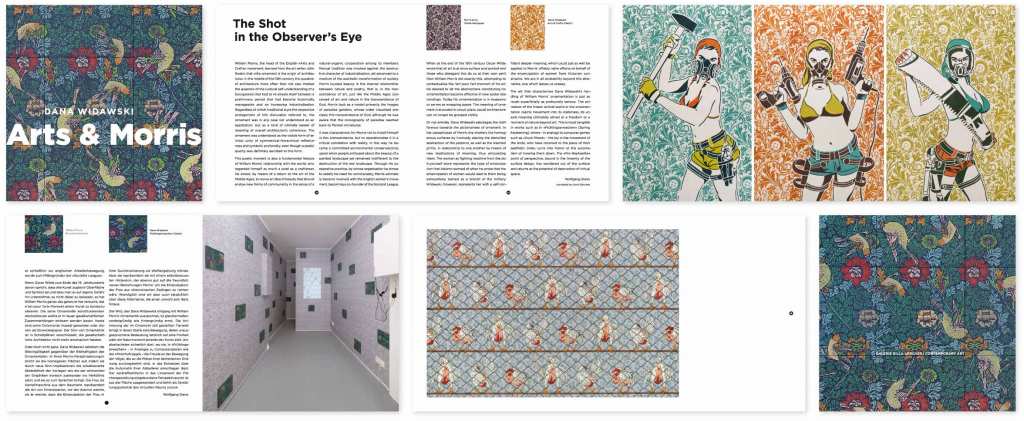

Arts & Morris

Exhibition catalog · Gallery Gilla Lörcher Contemporary Art · Berlin 2012

English/German · 20 pages · 5,00 € plus p&p

Review by Wolfgang Siano

download catalog «Arts & Morris» (PDF, 3 MB)

The Shot in the Observer’s Eye

William Morris, the head of the English «Arts and Crafts» movement, learned from the art writer John Ruskin that «the ornament is the origin of architecture». In the middle of the 19th century the question of architecture more often than not also implied the question of the cultural self-understanding of a bourgeoisie that had to re-situate itself between a preliminary period that had become historically manageable and an increasing industrialisation. Regardless of which traditional style the respective protagonists of this discussion referred to, the ornament was in any case not understood as an application, but as a kind of ultimate bearer of meaning of overall architectonic coherence. The ornament was understood as the visible form of an initial unity of symmetrical-hierarchical reflexiveness and symbolic profundity, even though a poetic quality was definitely ascribed to this form.

This poetic moment is also a fundamental feature of William Morris’ relationship with the world, who regarded himself as much a poet as a craftsman. He aimed, by means of a return to the art of the Middle Ages, to revive an idea of beauty that should endow new forms of communality in the sense of a natural-organic cooperation among its members. Manual tradition was invoked against the destructive character of industrialisation, art advanced to a medium of the aesthetic transformation of society. Morris located beauty in the internal relationship between nature and poetry, that is, in the transcendence of art, just like the Middle Ages conceived of art and nature in the transcendence of God. Morris took as a model primarily the images of paradise gardens, whose order visualised precisely this transcendence of God, although he was aware that the iconography of paradise reached back to Persian miniatures.

It was characteristic for Morris not to install himself in this transcendence, but to operationalise it in a critical correlation with reality. In this way he became a committed environmental conservationist, upset when people enthused about the beauty of a painted landscape yet remained indifferent to the destruction of the real landscape. Through his cooperative practice, by whose organisation he strove to satisfy his need for communality, Morris ultimately became involved with the English worker’s movement, becoming a co-founder of the Socialist League.

When at the end of the 19th century Oscar Wilde wrote that all art is at once surface and symbol and those who disregard this do so at their own peril, then William Morris did exactly this, attempting to contextualise the l’art pour l’art moment of his art. He desired to let the abstractions constituting his ornamentation become effective in new social relationships. Today his ornamentation is in museums or serves as wrapping paper. The meaning of ornament is encoded in circuit plans, social architecture can no longer be grasped visibly.

Or not entirely. Dana Widawski sabotages the indifference towards the pictorialness of ornament. In her paraphrases of Morris she shatters the homogenous surfaces by ironically placing the stencilled abstraction of the patterns, as well as the inserted prints, in relationship to one another by means of new implications of meaning, thus articulating them. The woman as fighting machine from the do-it-yourself store represents the type of emancipation that Adorno warned of when he wrote that the emancipation of women would lead to them being exhaustively trained as a branch of the military. Widawski, however, represents her with a self-confidant deeper meaning, which could just as well be applied to Morris’ affably naïve efforts on behalf of the emancipation of women from Victorian constraints. We are in all probability beyond this alternative, one which leaves us uneasy.

The wit that characterises Dana Widawski’s handling of William Morris’ ornamentation is just as much superficially as profoundly serious. The animation of the frozen animal world in the ornamentation injects movement into its staticness, its unsaid meaning ultimately aimed at a freedom or a moment of nature beyond art. This is most tangible in works such as in «Frühlingserwachen» [Spring Awakening], where – in analogy to computer games such as «Duck Shoot» – the joy in the movement of the birds, who have returned to the place of their aesthetic order, turns into horror at the automatism of mowing them down. The «Pre-Raphaelite» point of perspective, bound in the linearity of the surface design, has wandered out of the surface and returns as the potential of destruction of virtual space.

Wolfgang Siano

Berlin 2012

translated by David Sánchez